Kukri Info

Khukuri of the Month

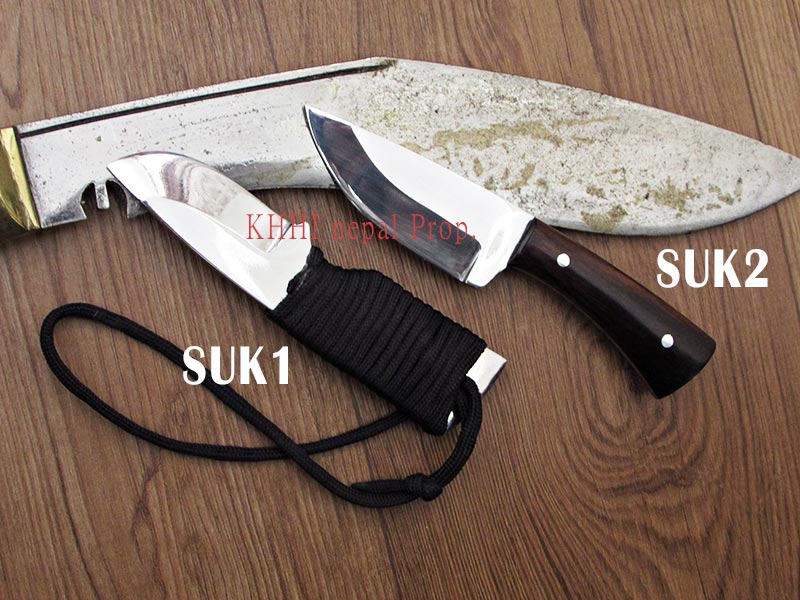

Blade Size (in): 2.5 in (SUKx 1)

Weight (gm): 100

USD 17.99

Honor of the Kukri

- Home

- Honor of the Kukri

The honor of the Kukri

Extracted from "The Gurkhas" written by "John Parker".

The revered kukri is to Nepal and the Gurkhas what the Sword of Honor is to Britain and such military institutions as Sandhurst (where the Sword of Honor is awarded to top graduates).It is a symbol of great respect and high public regard for those fighting men who have passed with battlefield honors and special distinction in the military service of their regiments and country. For this reason the kukri has been adopted as the officer classes are distinguished in rank by differently graded kukris, and where a kukri is used to symbolize the King’s presence.

In Evelyn Waugh’s novel Officers and Gentlemen, the second part of his Sword of Honor trilogy, it is suggested that ‘there should be a drug for soldiers…to put them to sleep until they are needed. They should repose among the briar like the knights of the Sleeping Beauty; they should be laid away in their boxes in the nursery cupboard.’ And this is precisely what is done with the regimental kukri when it is not needed, when it is put away in its scabbard and used purely for ceremonial or symbolic reasons.

In Evelyn Waugh’s novel Officers and Gentlemen, the second part of his Sword of Honor trilogy, it is suggested that ‘there should be a drug for soldiers…to put them to sleep until they are needed. They should repose among the briar like the knights of the Sleeping Beauty; they should be laid away in their boxes in the nursery cupboard.’ And this is precisely what is done with the regimental kukri when it is not needed, when it is put away in its scabbard and used purely for ceremonial or symbolic reasons.

I put it to Colonel Dawson, the Brigade Secretary of the Royal Gurkha Rifles in Britain, that the kukri is much more than a weapon of war and that it seems to symbolize the respect felt for those who have fought for the honor of their regiments in the service of the British Crown. For a soldier t have a kukri, or to wear it in the form of an emblem, he must achieve more than other soldiers by getting into and distinguishing himself in the Gurkhas. He must be deserving of that honor and prove himself worthy of his kukri, from which in Nepal, he must never be parted, and he is under a moral obligation to use his kukri bravely in times of war.

But the colonel’s response to this is not enthusiastic: ‘Overstated, I feel.’

The kukri is, in many respects, the Gurkha soldier’s honors degree. Whether or not, in all honesty, he seriously believes in the kukri as such an honorable emblem or distinction is not the point, because that is what, through its legendary history, it has become- that is what, by tradition, it represents. It is the stuff of legend and popular mythology, as well as a military distinction, and the spell that it casts is psychological. It is bigger than the man, on whom the distinction is conferred, representing much more than an all-purpose tool and military weapon.

This is how many interpret the extracurricular significance of the kukri: as an icon of military culture, both in the national psyche of Nepal and in the regiments that have lived by it as surely as others have lived by the sword. But how does Colonel Dawson interpret the kukri? He tells me: ‘The kukri is a tool and is used as such. It has no particular significance other than as a working tool. In Nepal it may have come to be regarded as an icon, but much of the above overstates the case.’

So much is said about this world-famous and oddly curved little fighting knife, which has become the symbol, not only of Nepal but also of the Royal Gurkha Rifles in the UK, with its two battalions, one in the UK and one in Brunei. It is as symbolic to Gurkha men of war, and the Nepalese nation and its various tribes today, as are the spear to the Zulu and the sword to the Samurai. It would seem to stand for an idealized concept of bravery and method of fighting, for heroism and honor in gruesome hand-to-hand fighting by men of determination and faith- faith in them to be able to defend themselves, faith in the rightness of their cause, and above all faith in the outstanding martial history and purpose of their race.

The kukri also seems to stand for an idealized past. To the nostalgic minds of those who prefer the kukri to the machine age tank, it is a more honorable weapon, cleaner, nobler, braver and more dignified than the tank, because one must have the guts to engage one’s opponent, eyeball to eyeball, in fair and equal combat. (Truth to tell, soldiers who take this view may also believe that the kukri is more fun than the tank.)

When we talk of military honor we talk of good personal character, of loyalty and honesty, of honorable and uncowardly conduct on and off the field of battle, of upholding the honor of the regiment, and respect for all that is perceived to be honorable. But if these values are not to be false – if this talk is to be anything more than hollow – they have to be backed up with action. In the case of the Gurkhas, “kukri action”; because it is a romanticized symbol of honor that has captured the imagination of the entire world, this glittering and much-revered little weapon is nowadays used as much for ceremonial purposes as it is for hand-to-hand fighting. And, in the country in which it originates, its most common use is for neither of these purposes, but for everyday tasks such as cutting and butchering meat, skinning animals, peeling vegetables, and hacking, shaping and chopping wood. It is used for these tasks by both the valley dwellers and the hill peoples of Nepal, many of whom still carry it around with them in their belts or sashes, and by all accounts it has been in use there since the seventeenth century.

In short, the kukri is an all-purpose tool and the purposes to which it is put are as peaceful as they are warlike, as domestic and civilian as they are military. The kukri is at the very heart of the tradition and culture of Nepal, and, as a very good friend or a deadly foe, it mirrors the duality of human nature and the nature of mankind.

But to return to the kukri’s more elevated uses, we can see that its historic renown as an instrument of war is matched only by its significance in ceremony and ritual. In royal ceremonies the kukri is predictably splendid and can inspire even spiritual and mystical qualities. It is for this reason that, when the King of Nepal is unable to attend any ceremony or festival in his palace, his own golden kukri is placed on his throne, so that he can be there in spirit. Reverence and obeisance are paid to him through his kukri, such is its intended spiritual power.

On these enchanting royal occasions, when the King’s kukri is placed on his throne by his ministers of members of his family, the knife is transformed from a weapon of war into an emblem of peace and enchantment. In this role it reflects veneration, awe and deep respect for the crown, culture, customs and traditions on behalf of which it has been used to savagely in so many wars throughout the centuries. But in battle it has wielded a lurid and lethal enchantment: against Turks, Germans, Italians and Japanese, Persians, Arabs and North Africans, Koreans, Malaysians and Indonesians, to mention but a few.

And from all these bloodbaths it has proudly emerged, gleaming once again, cleansed of all its enemies’ blood, to survive as an eternal symbol of the determination, honor and manliness of the Gurkha soldiers and the Nepalese nation. The earliest known kukri, owned by Gorkha king, Rajadrabya Shah in 1627, can be seen today in the National Museum in Kathmandu ( also on display there is another eighteenth-century heavy-duty kukri, dating back to 1749,which was the property of Kanji kale paned and is much heavier than today’s kukris.

It is said that the kukri came into its own against the long spears, two-edged long swords, wrist-guard short swords and knives of Prithvi Narayan Shah’s opponents. These weapons were no metal for the versatility of the kukri, and could not parry this curved little knife satisfactorily, if at all. Because of its efficiency in hand-to-hand warfare, the kukri quickly became the preferred and fabled weapon of Nepal. The shape and structure of Rajadrada shah’s kukri has hardly changed at all since 1627 and I am tempted to suppose that its peculiar curved blade is shaped to follow the line of an opponent’s neck! I have absolutely no proof or evidence of this, but why else would it be curved?

Kukri blades are made of steel and the best-quality examples today are those of European steel, whereas kukris made in Nepal are of poorer steel. Handles are usually made of wood or buffalo horn. Today’s kukris remain broad-bladed, just as they were in the seventeenth century, with the same grooved cutting edge, and the same handles and notch at the base of the blade. The handle of Rajadrabya Shah’s kukri is of carved wood, as would have befitted a Gorkha king in those days. While these days they are ivory, heavy metal and other handles. I am told that the grooved cutting edge is designed to cleverly deflect and so reduce the impact of a blow from an enemy’s saber, sword or knife by tilting and turning it aside instead of meeting it head on. The kukri user briefly lets the diminished force of the blow vibrate all the way down the blade to the notch at its base, then gives a quick twist of the notch to unbalance the offending saber, sword or knife and disarm the enemy.

The Gurkha Museum in Winchester describes the action of the kukri thus: ‘A notch in the blade close to the handle serves the purpose of preventing blood from reaching the handle and is also symbolic of the Hindu Trinity of Bramah, Vishnu and Shiva. Two small knives are fitted at the top of the scabbard, one blunt (Chakmak) and the other sharp (Karda). The correct use of the former is for starting a fire with a flint stone and as a sharpening stone, and the latter is a skinning or general purpose knife… The wrist action with which the kukri is wielded makes it extremely effective in the hands of one accustomed to using it… there is also a sacrificial kukri with longer blade and handle suitable for gripping with two hands… little used except for sacrificing animals at festival time. The popular myth that blood must be shed every time a kukri is drawn from its scabbard is untrue and probably stems from the fact that if drawn in anger, then it was unlikely to be replaced without being used! Similar stories of the kukri being used as a throwing knife can be disbelieved.’

In the Nepalese Army, high-ranking officers are distinguished by the exquisitely tasteful patterns etched into the blades of their kukris. Senior members of Nepal’s royal family have similar but even more splendid etchings on their kukris. Army officers’ kukris have semicircular insignias, while those of royalty bear circular insignias designating high caste. The idea of royalty and army wedded together, the latter in the loyal and devoted service of the former is symbolized by these priceless and decorative kukris, some of the handles of which are inlaid with emeralds and other precious stones.

The scabbards for these very superior kukris feature gold and silver mountings, whereas most standard scabbards are made of wood, leather or bone and incorporate very useful tiny pockets – not unlike miniature bullet pouches- into which tweezers, pen knives, nail clippers or scissors and the like can be inserted. The more decorative standard scabbards are inlaid with brass, colored glass, turquoise or lapis lazuli, and some of the ivory kukri handles imitate animals’ heads. But, whatever materials are used for the scabbards and handles, and whatever designs are employed to beautiful these; there is no getting away from the fact that the kukri remains a lethal fighting knife. Similarly, however mystical it may become in the ceremonies of Nepal and the Gurkha regiments wherever they may be serving in the world, there is of course nothing in the least mystical or ceremonial about the use to which the kukri is put in military combat. One must remember this famed efficiency when releasing a sharp kukri from its scabbard. The back, or blunt, edge of the knife is held towards the body, so that the cutting edge is facing away from it.

So much for the military, ceremonial and domestic uses of the kukri but it is also used for religious purposes, demonstrating yet again its spiritual significance in the overall scheme of things in Gurkha and Nepalese minds.

The Kukri is used for severing the heads of buffalo, sheep and goats at religious festivals, where it is thought that the higher the blood spurts into the air, the greater the blessings that rain down on the people. It is also used to spill animal blood and God’s blessings on weapons of war, and here again we are reminded of its dual role as a spiritual symbol and a military tool.

The emblem on the badge of the “Royal Gurkha Rifles” in Britain shows two upturned kukris meeting at the top, their naked blades crossing, as if to convey a pledge from those whose profession it is to use the kukri when fighting for the honor of the regiment and in the service of the British Crown: ‘Cross my heart and hope to die!’ or, to quote the actual regimental motto, “Better to die than to be a coward”.

Share